Tentcraft

Lisa Kelly & Alex Gawronski

SOUTH

30 march – 10 april 1999

Sydney

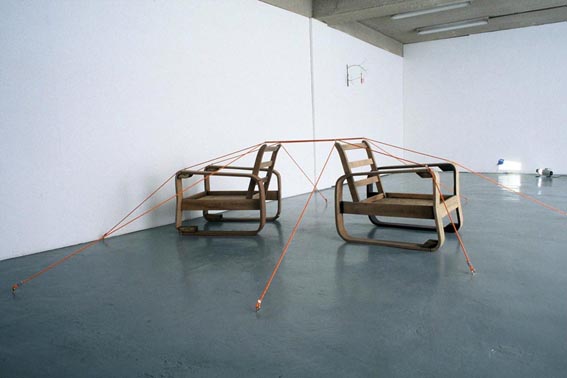

1. Life Security 1999 (with Alex Gawronski)

found chairs, nylon rope, dyna-hooks, hardware

2. Ljus Och Viss Varme 1999

twig, camping lantern, citronella candle, hardware

3. Cobweb 1999

projector, spider, glass slide, plastic, dowel, acrylic, cork, adhesive mesh

4. Burning Desire 1999

cyalume light sticks, dowel, blutack, hardware

[all photos: Christopher Snee]

catalogue text

Alex Gawronski & Lisa Kelly (italics)

A working motivation unravelled from the container of a word.

t e n t c r a f t

faded advice soon re-developed amid Parramatta Rd.

Thinking of movement, a conflict of mobility and stasis,

and the parallel world of stuff that crafts a migration elsewhere.

Camping is a word embroidered with numerous associations. It is inscribed with various international codes that nevertheless belie a desire for universalism. It is colour coded, bound up yet it suggests escape and freedom, freedom from life. When we take off we hope equally to get lost, without necessarily abandoning the familiar texture of our lives back home. Indeed it is familiar difficulties of the emotional, financial and social kind that we seek to replace with the difficulties of a sort we can readily overcome. These are primarily practical difficulties. What they represent is an A-Z guide on how to: stay dry, stay warm, keep cool, avoid bites, avoid falls, maintain orientation, remain mindful of the environment and of our co-travellers and of ourselves. At the same time we seek to erase temporarily our local presence and to become (if only partially) wild. The camper seeks a reunification with those things that he or she takes for granted, those things technology keeps us safe from whilst seeking to maintain our complicity with our natural selves.

Polartec, mylar, cyalume, gore-tex, neoprene.

A wonderland on offer at the Kent St. strip.

An essential, portable two-toned world.

What you need in retreat from what you have.

Today more than at any other time the natural self is under scrutiny. Today the natural self requires a whole range of paraphernalia in order to return to and acknowledge the sanctity of the natural other. What the camper seeks is not only the reassurance of the practical, but the codified glamour of the fashions and tools of mastery. The elements may press close, they may seek to disrupt and disturb our equilibrium half way up a mountain, dangling from ropes or way down a crevice. It is in moments like these that we seek the reassurance of everything technology can do for us. It can save us. Its materials are alternately ultra light and ultra warm. Technologically enhanced food may appear unappealing at first yet we can carry twice as much whilst seemingly surviving on half the amount. We become both bigger, stronger, more enduring at the same time as appearing smaller, less significant, ultimately humbled in the face of nature.

To camp in a life, cast a charm of the temporary

onto a life’s tethered net of contents.

Resistance as a mesh on approach, a scent to repel,

the slender safety structure held up against veiled danger.

A spider’s skin adrift in Power library,

the salvaged shadow of a threat.

Of course not all camping is about the heroism of dramatic exploits. Camping also comforts. We are comforted by the illusion of having next to nothing. We are comforted by our sense of immersion in the elements and of the benefits of the manual traversal of the countryside. The iconography of the tent for instance restores images of original dwelling. It magnifies a sense of security in the very notion of dwelling by reducing it to its simplest representation. We inhabit this representation like an imagined collective memory. At this instant we become more explicitly participants of culture through our apparent renunciation of it. We are housed by the idea that we will remain housed by the culture we are a-part of.

Travelling light. The pleasing incline offered by a tent’s shelter,

a diffused elsewhere light.

Firelight, tentlight, torchlight.

Leaving the security of our abodes is equally the source of humour. The failed or discarded attempt at leaving it all behind is a reminder of our comic potential and the over-inflated sense of our own primitive ability. Likewise to inhabit the gallery is to rehouse ourselves temporarily. The gallery becomes the site of mobile narratives that enable the idea of dwelling to resonate. Like a nomad, the artist skips contexts in order to maintain an active engagement with the culture in which he or she is immersed. At the moment of engagement we realise the absurdity of the context and the long since problematic neutrality of the institution. As an antidote to this we address the sites peculiarity, its extraordinary aspect. In the end this may appear as familiar to us as the most frequently quoted urban myth. However it is such myths that allow us to de-site ourselves as we step from responsibility to consider our responsibility to notions of place. Here we embark upon an adventure laced with speculative dangers.

As they thought of tents they talked about light,

and really it’s mostly light.